IBM’s efforts to expand the use of its Power chips in hyperscale data centres just got a big shot in the arm from Google.

IBM’s efforts to expand the use of its Power chips in hyperscale data centres just got a big shot in the arm from Google.

The online giant showed its first home-built server board based on IBM’s upcoming Power8 processor at an IBM conference in Las Vegas yesterday.

Google is a founding member of the OpenPower Foundation, IBM’s project to open up the design of its Power chip for use in new types of servers, so it’s no secret Google was on board with the effort. But it hadn’t confirmed publicly that it was building Power hardware and porting its software to the chip.

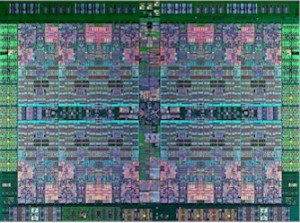

On Monday, Gordon MacKean, a Google engineer who’s also chairman of the OpenPower Foundation, posted a picture of Google’s Power8 server motherboard on his Google+ page.

It’s a test vehicle, so it doesn’t mean Google will roll out Power servers widely in its data centres any time soon, but it’s a good vote of confidence for IBM.

“We’re always looking to deliver the highest quality of service for our users, and so we built this server to port our software stack to Power,” MacKean wrote.

“A real server platform is also critical for detailed performance measurements and continuous optimisations, and to integrate and test the ongoing advances that become available through OpenPower and the extended OpenPower community,” he wrote.

Power chips are used primarily in IBM’s own Unix servers, but declining sales of those systems has forced IBM to look farther afield. By licensing the design of Power8, it hopes to persuade other companies to design Power chips and servers for use in other markets.

It will compete in those markets with Intel’s x86 Xeon chips, which dominate today, and also with 64-bit processors from ARM, which are slowly making their way to the server market.

Indeed, ARM chips have been getting most of the headlines lately. Like Intel’s Atom processors, they’re not powerful but are seen as a good fit for workloads that involve high volumes of small transactions, because their small cores consume little electricity.

But there’s a place in hyperscale data centres for beefier cores, too. Processors like Xeon and Power support high core counts, fast bandwidth on and off the chip, and large memory footprints, which are good for analysing large amounts of data quickly.

Porting Google’s software to Power was easier than expected, MacKean wrote, thanks in part to the support in Power8 for “little-endian,” a data format used by x86 processors.

He didn’t say anything else about the board, except that it’s being shown off in the OpenPower booth at IBM’s Impact conference in Las Vegas.

IBM still has work to do as it tries to build a new ecosystem around Power. It will need companies with a different cost model from IBM’s that can produce Power chips and servers cheaply enough for companies like Google and Facebook to buy.

Those companies like to design their own low-cost hardware and don’t want all the bells and whistles that the IBMs of the world provide. IBM has signed up one chip licensee so far, China’s Suzhou PowerCore, as well as a few systems builders, including Tyan and Hitachi.

There are about two dozen members of the OpenPower Foundation altogether, including GPU vendor Nvidia, InfiniBand vendor Mellanox, Ubuntu Linux maker Canonical, and other software and component companies.