On the face of it, blockchain has the potential to fulfill some of Saudi Arabia’s most important Vision 2030 goals.

The strategy, announced in 2016, lays out a broad economic and social transformation plan, with technological development as one of its main strategic pillars. The Vision 2030 blueprint says the Kingdom will “expand the variety of digital services to reduce delays and cut tedious bureaucracy” and will “immediately adopt wide-ranging transparency and accountability reforms”. Blockchain ticks both these boxes.

However, as many enterprises and governments in the Middle East are beginning to discover, introducing blockchain systems isn’t straightforward. A lack of developer expertise and suspicion from third party partners have been two of the biggest hurdles to widespread adoption so far. Saudi Arabia, like so many other nations and private sector enterprises, is still finding its feet, but is determined to put blockchain at the core of its operations.

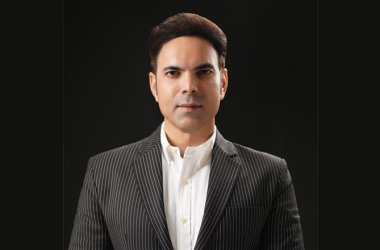

Dr Hesham bin Abbas, head of Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology’s blockchain initiative, a speaker at the recently held Unlock Blockchain Forum, concedes that Saudi Arabia is in the “exploratory” phase with blockchain, but believes the country is not alone in this regard. “That’s the same for almost everyone across the world,” he says. “Some use cases are under development in different areas and entities in Saudi Arabia. Some are in areas like telecoms and municipalities, where we’re piloting some projects but are working towards finding the right use cases. It’s good to understand the benefits and drawbacks of blockchain at this stage.”

Bin Abbas, who obtained his doctorate in computer networks from the University of Pittsburgh, and also holds degrees from King Saud University and the University of Washington, believes that blockchain will be an ideal fit for the country, and an important strategic component of its development. “Saudi Arabia is interested in the enablement of all emerging technologies, and this especially applies to blockchain, which is an important part of our economic diversification,” he says. “Most of our revenue growth will come from emerging technology. Traditional areas such as software, hardware, services and cloud are mature and saturated. Vision 2030’s main strategic objective is non-oil economy diversification. Digital transformation is one aspect of that, and we see major opportunities with emerging technologies.

“We believe we have a really good opportunity with blockchain. It has many advantages like transparency, speeding up processes, cutting costs and delivering a trusted environment for all stakeholders. All these features are aligned with our government and its goals.”

Experts have hailed the collapse in cryptocurrency prices in November 2017 as being the turning point for understanding their underlying technology, and this shift has served not only to give a less cynical interpretation of blockchain, but has also increased the understanding of the value it can provide. “When cryptocurrencies became very high-profile a few years ago, there was a lot of confusion around blockchain,” bin Abbas says. “Now, I think it’s become clear to everyone how to differentiate between the technology and its misuse. Any technology can be misused, and the perception of Bitcoin being associated with illegal activity definitely affected it.”

Unlike the Dubai government, which has given a mandate for 50% of government services to be blockchain-based by 2020, bin Abbas believes Saudi Arabia will evaluate whether to use blockchain on a case by case basis and does not believe it will be a bureaucratic panacea. “Blockchain doesn’t solve every problem,” he says. “There are certain conditions for which it will be the right solution, but they need to be identified correctly. Sometimes, you won’t need to invest in blockchain at all, and a traditional application or database will be good enough. You need to work with potential users to understand the right scenarios. The irrevocable nature of information within blockchain isn’t an advantage or disadvantage, it just depends on your application requirement. If your requirement is for information to be unchangeable then it’s the right option. It depends on your business requirement and the application itself.”

Identifying the appropriate use cases for blockchain is all well and good, but the world already faces a huge shortage of skilled developers that are able to meet fast-growing demand. The world’s tech powerhouses are beginning to announce their play in the space, and some companies may even have to learn on the job in order to meet market needs. Saudi Arabia wants to make sure it is equipped with the right talent to build the necessary foundations for blockchain development.

“We’re committed to implementing all the right ecosystem components,” bin Abbas says. “MNCs are essential, and we’d like to develop a strategy which promotes them investing in Saudi Arabia and working with the government. We also want to develop local talent and startups. Some of the blue-chip tech companies are already here and have created a business line for blockchain, but we’re also targeting small international startups that have strong expertise. We’re trying to find the best way to collaborate and create the best opportunities to do business.

“One approach is to explore the demand and supply aspects of Blockchain in parallel. On the demand side we could hold sessions and workshops with different sectors to identify the right use cases, implement a high-level architecture then come up with clear demand for use cases. On the supply side, we could work with local entrepreneurs to engage in incubators and accelerators. You can then match the supply with demand with the help of a regulatory framework.”

A key part of Saudi Arabia’s blockchain journey will be played out beyond the PC monitors of application developers and instead between regulatory committees that must decide upon the rules that will govern the technology’s usage. Blockchain, by its nature, must have regulations that are compatible with a country’s international partners.

“Blockchain is borderless – it can’t have conflicts with international interests,” bin Abbas says. “Regulatory frameworks and standards are not internationally developed yet, so we’re going through a journey of use cases, and are collaborating with international companies and delivering education and awareness sessions to understand the value of the technology. This will all help us to identify challenges and learn from experiences to understand how to design frameworks for standards and policies that align with international trends and help to develop local talent.”

Saudi Arabia also has plans to introduce broader changes around citizen information that relate to the use of blockchain. “We also want to deliver open data, data privacy and data security,” bin Abbas says. “These are strategic policies we’d like to align with blockchain.”

Paradoxically, although blockchain is intended to increase trust amongst concerned parties, one of its biggest obstacles to success is exactly that – trust. IBM’s highly publicised partnership with logistics giant Maersk is the world’s most renowned blockchain use case, but the deal has run into difficulty in terms of onboarding smaller partners to the platform. “There are definitely limitations, difficulties and technical obstacles around blockchain,” bin Abbas says. “You can already see some of the issues that the world’s biggest companies are facing with blockchain, but that’s natural. You have to expect some limitations and issues. They will be solved and resolved with the right R&D and protocols. Blockchain’s potential opportunities are bigger than its expected obstacles. Blockchain doesn’t appear all of a sudden as it’s an integration of existing technologies to develop new services.”

Bin Abbas does not believe that a decentralised ledger technology could pose a significant threat to traditional transaction custodians, such as banks. Central governments across the world have considered the threat to their existence, but bin Abbas believes the most essential institutions will not be affected by its introduction. “I don’t believe they’re under threat because it ultimately depends on the application that you use,” he says. “I don’t want to call blockchain a threat, because I believe businesses will adapt to new technology. However, sometimes, keeping control of everything is an overhead cost. Maybe it’s better to release control of certain things, and blockchain can certainly assist with that. Businesses like banks and central governments will be needed, and that won’t change. You can’t just move everything to a blockchain solution. If you need to get rid of a central authority then you could use blockchain, but if you do then maybe it should be a private, permission-based blockchain, which is similar to existing databases.”

However, bin Abbas acknowledges that smaller organisations that have historically been responsible for managing transactions could find themselves threatened by blockchain. “It’s true that smaller businesses such as currency exchange houses could be at risk,” he says. “Many banks themselves are investigating things such as currency remittances through blockchain. Globally, banks are trying out different solutions. Ripple has already signed agreements with more than 1,200 banks around the globe, so I think banks see blockchain as more of an opportunity than a threat.”