In ancient Greece, the goddess Panacea represented universal remedy and health. Along with her four sisters, they were symbols of cleanliness, recuperation, healing and glory. Panacea, in particular, had the power to heal the sick through the mythical potion she possessed.

It seems ironic that in 2017, one of the world’s most promising technologies, although far from being a universal cure for the ills of so many industries, is serving a purpose that Panacea would have undoubtedly been proud of.

In July, doctors in Dubai succeeded in saving the life of a 60-year-old woman who suffered from a cerebral aneurysm in four veins – causing life-threatening bleeding in her brain – with the help of a custom 3D-printed model of her arteries.

Due to the rarity of the patient’s case, Rashid Hospital’s interventional radiologist Dr Ayman Al Sibaei needed a 3D model that would deliver a visualisation of exactly how his team could safely reach the arteries. The six-hour operation proved a success, and the 3D-printed model was ultimately a vital factor behind that.

It is not the first time that the Dubai Health Authority has conducted complex surgery with the aid of 3D printing. Doctors also succeeded in removing a tumour from a patient’s kidney with the help of a cutting-edge aid — a custom 3D-printed organ to help plan the surgery last December.

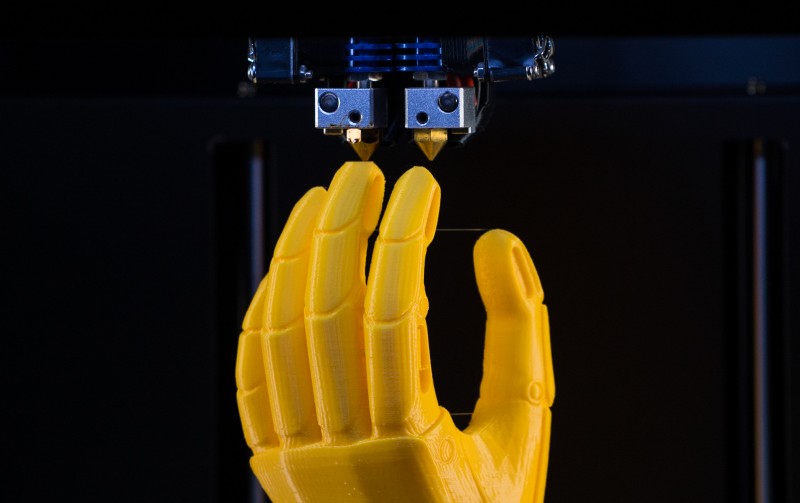

The Authority has also given its hospitals a mandate to print artificial limbs, denture molds, fracture casts and models of organs for patients to simulate surgery before actual procedures.

In May, Dubai resident Belinda Gatland received the region’s first-ever fully 3D-printed prosthetic leg. A horse racing accident in her early 20s had left the British expat in pain for nearly two decades; the bones below her knee had shattered “to smithereens”, and necrosis, or the premature death of tissue set in. After nine unsuccessful operations, she finally opted to have the leg amputated and replaced with a 3D-printed prosthetic limb.

A 3D-printed prosthetic leg with the same functionality as high-end conventional ones costs between AED 40,000-50,000 – up to 50 percent cheaper.

Shadi Bakhour, Canon Middle East’s B2B business unit director, certainly agrees that healthcare is the prime candidate to be most transformed by 3D printing. “It is the one sector where the true substance of 3D printing will materialise,” he says. “3D-printing human body parts to replace costly prosthetics, as well as human organs, will change lives, especially as the technology becomes more accurate.”

He goes on to add that localised 3D printing services will make parts more easily available in the Middle East, speeding up the end-to-end process of medical operations. “In the future, we could have an outsourced service centre a few minutes away from the hospital, where doctors in the UAE could obtain a human organ model. 3D printing could also help reduce the time to perform surgery, such as organ transplants, by providing highly accurate 3D imagery, and as a consequence reducing the cases of complications arising from the procedure.”

“It can already be said that the most exciting advances in 3D printing can be found in the world of medicine, where 3D printing is starting to revolutionise how we treat patients,” Autodesk’s territory director for the Middle East and Turkey, Louay Dahmash says. “The solutions on offer are still in their experimental stages, but first tests are looking promising in a variety of areas such as 3D-printed prosthetic limbs and 3D-printed skin for burn victims. The industry has adopted 3D printed solutions due to the technology being cost-effective, and the fact that items can be assembled directly from a digital model, increasing precision and removing room for error.”

According to Canon’s 2017 3D Printing Insight Report for the Middle East, spending in 3D printing is expected to have a compound annual growth rate of 30 percent in the region, outperforming the worldwide growth rate of 26.9 percent. IDC, meanwhile, believes that spending on 3D printing in the Middle East and Africa is set to increase from $470 million in 2015 to $1.3 billion by 2019.

Government enthusiasm is certainly not lacking in the GCC’s technology hub. The Dubai government’s 3D-Printing Strategy was unveiled in April 2016, and aims to make the emirate a global capital of the technology. A month later, the city inaugurated the world’s first 3D-printed office in Downtown Dubai. The city’s government has also set an ambitious target of having 25 percent of buildings in Dubai being built using 3D printing technology by 2030.

Away from the operating table, however, other industries are yet to fully immerse themselves in its undeniable potential. Concerns around cost endure, as well as the risks of delivering product accuracy.

Bakhour believes there are a range of issues around product specificity and price that are currently holding regional organisations back from taking the 3D plunge. “3D printing is done with a limited choice of materials; currently most 3D printers use plastic, ceramics, polymers and metals,” he says. “To an extent, 3D printers still have relatively poor parts accuracy, insufficient repeatability and consistency, and lack in-process qualification and certifications. The current price of industrial 3D-printers and printing materials can also hold back their more widespread adoption.” He does, however, believe these issues could be solved over the next “5-10” years.

Dahmash believes that the biggest hurdle is one of attitudes towards the technology. “The challenge is to get the wider pool of professionals within the industry to expand their thinking, and open up to the ideas and opportunities that 3D printing can provide across a variety of industries, whether it is design, manufacturing or construction.”

Bakhour agrees, saying that although the means may exist to deliver 3D-printing technology, the spark of genius often needed to find innovative uses to apply it is lacking. “While there is work to improve the accuracy and materials in 3D printing for instance, there is still a gap in the actual creation of content and design,” he says. “How are we going to transform an idea into a 3D-printed object without the actual content? That is where the gap lies to really see the full potential of 3D printing.”

It could be argued that, for the time being at least, this thinking may not change as the agents for it simply aren’t present in this part of the world. Bakhour certainly believes that the region currently falls short in that regard. “In the Middle East, there are some gaps such as lack of local presence from 3D printing vendors,” he says. “This slows down market development, consumables’ availability and post-sales service and support. This always results in relatively higher hardware and consumable prices compared to North America and Europe.”